I didn’t start writing songs I was proud of until I was 30. Before that, it was all trial and mostly error. Trying to write like Waits. Or Lucinda. Or Bruce. The songs that came out were possibly charming, possibly even interesting, and definitely derivative. In trying to find my own voice, there was always an inauthenticity. They never felt honest.

While I couldn’t put my finger on it at the time, there was this tension between writing about what I actually felt, and writing about what I *should* be writing about.

Both options weren’t great. What I felt wasn’t particularly interesting or of concern to people looking to emotionally connect with music and see themselves reflected in characters. Would I just write about the boring and entitled woes of an upper-class kid who had gone to fancy schools? Would people care about that? I wouldn’t.

The other option had promise. The one potential source of tension in my life, the one brick that didn’t so neatly fit into my otherwise intact wall of American-ness, was the fact that I’m Arab American, born to Palestinian parents who fled war as children. In a post 9/11 country, maybe that was a thing to explore. The problem was, at that age, I didn’t really feel it. I had of course gotten some crap for my funny name and was bullied a little growing up, but I look more white than what someone might think of as ‘Arab.’ I walk through the world effectively as a white man. I couldn’t claim to suffer as a minority when I didn’t look like one, nor have the lived experience of one.

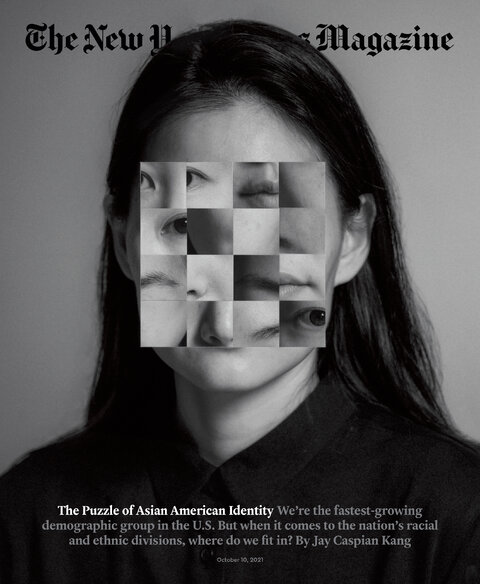

Still, any outside observer would clasp their hands and say “ooh that sounds juicy, go with that.” The New York Times writer and my former college roommate Jay Caspian Kang was one of those observers, making the case to me in an Allston bar in 2002. He recounted our debate in that bar honestly and beautifully in a broader New York Times Magazine piece about what it means to be Asian-American, and what it means to assimilate. Our argument unfolded in the context of Springsteen, and could’ve been about any prompt to explore issues of identity and American-ness.

Apart from enduring the awkwardness of reliving that time of my life (see photo – I had a soul patch), I ate Jay’s piece up. And I now realize the importance of asking the questions I should have been asking at 25. Why not explore identity, even if I don’t appear to embody a singular version of it? Why not unpack the messiness of being hyphenated, especially when either side of that hyphen comes with caveats? Wouldn’t it have been interesting to ask why Springsteen resonated with me and not with someone like Jay? Just what role does my ability to ‘pass’ as white play in that?

They are big questions, maybe impossible for a 22-year-old to answer. Jay writes that he regrets putting me on the spot: “The memories of this conversation make me clench with embarrassment — the bald vision of identity, the reduction of a friend into the version of himself that would have been most profitable.” And still, they were so important to ask, even at the time when we both admittedly didn’t have the vocabulary to do it eloquently.

I ended up asking them on Kingsley Flood’s more recent albums – Another Other is the most personal thing I’ve done, Neighbors and Strangers attempts to document an immigrant experience similar to those of my parents and my in-laws – and still, thinking about that debate with Jay in that bar in 2002, it’s striking to grasp how long it takes to unpack these questions. And it might do us all good to offer a little grace to those of us still trying to answer them. Honestly, at least.

(The NYT article came from Jay’s book, The Loneliest Americans, which is out today…go get it).